Northern Shrike

General Description

This medium-sized, gray songbird is the larger and paler of the two species of shrike in North America. The Northern Shrike has a light gray underside, and a darker gray back. Its wings are black with white patches, and its tail is black with white corners. It has a large bill that is hooked at the end, and a narrow, black mask across its face. The female is slightly browner with a less distinctive mask than that of the male. Young birds are almost totally brown. Their wings are dark, but when they are folded up on the perched bird, they can be difficult to see and use as a fieldmark. The juvenile also has a less obvious mask, a paler bill, and barred underparts. Northern Shrikes, in comparison with Loggerhead Shrikes, have larger bills and narrower masks. Northern Shrikes occur in Washington only during the non-breeding season; for most of the year, they do not occur in Washington at the same time as Loggerhead Shrikes.

Habitat

Found all across the Northern Hemisphere, Northern Shrikes breed in northern boreal forests in semi-open areas along streams or edges. They winter in open lowlands, but prefer areas with more tree and shrub cover than those frequented by Loggerhead Shrikes.

Behavior

Northern Shrikes need large territories and thus are found only in low densities. They hunt by watching from high perches, then flying swiftly down after prey. Shrikes use their hooked bills to break the necks of vertebrate prey. Because their feet are not large or strong enough to hold prey, shrikes find a crotch in a tree, a thorn, or barbed wire to hang their prey on while they eat. Prey may be left on such a site for later consumption. During courtship, males sing to defend their territories and attract mates. Their song is complex and often includes imitated parts of other birds' songs.

Diet

Northern Shrikes eat mostly small vertebrates, especially voles and other rodents. They also eat small birds and large insects, and can kill prey as large as they are.

Nesting

Both sexes probably help with nest building. The nest is usually located in a low tree or large shrub, 6-15 feet above the ground. The nest itself is a loose, bulky cup of twigs, grass, bark, and moss, lined with feathers and hair. The female incubates 4-7 eggs for 15-17 days. Both parents feed the young, which leave the nest at 19-20 days. The parents continue to feed and tend the young for another 3-4 weeks.

Migration Status

Migration occurs in mid-fall and early in spring. Numbers on the wintering grounds can vary considerably from year to year, with large numbers occurring in invasion years.

Conservation Status

Christmas Bird Count data reveal a decline in wintering birds in Washington. Oregon, however, has seen a slight increase, which may reflect a shift southward. Many populations of Northern Shrikes around the world are in decline, and while there is no clear evidence of decline in North America, this species should be monitored carefully.

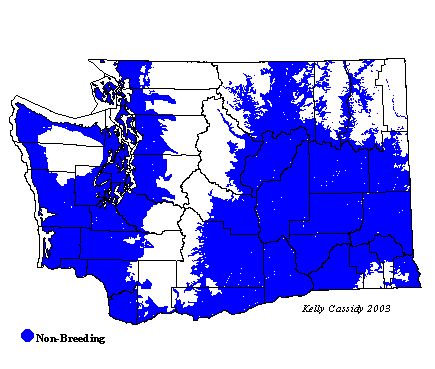

When and Where to Find in Washington

Winter visitors, Northern Shrikes can be found in Washington from late October to mid-April in appropriate habitat throughout the state. Their abundance varies, but they are typically more common in eastern than western Washington, and more common early in winter rather than later. In the shrub-steppe zone, Northern Shrikes are one of only a few species of songbird present in winter.

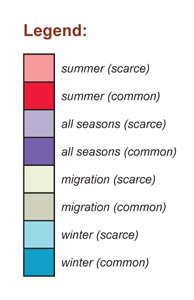

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | U | U | U | R | R | U | U | U | ||||

| Puget Trough | U | U | U | R | U | U | U | |||||

| North Cascades | R | R | R | R | U | U | R | |||||

| West Cascades | R | R | R | R | R | |||||||

| East Cascades | U | R | R | R | U | U | ||||||

| Okanogan | U | U | U | U | U | U | ||||||

| Canadian Rockies | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | |||||

| Blue Mountains | U | U | R | R | R | U | ||||||

| Columbia Plateau | F | F | F | U | F | F |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map